DLTK's Blog, Writing, and Poems

"Everything I am Inside"

A short critical essay on self-love/-care

September 20, 2018 - Toronto, Canada

I've had a difficult year, and it's not something I wanted to talk about or write on. Nonetheless, the consistent stream of self-love rhetoric that I see on social media has served as a convincing juxtaposition to my current situation and is causing me to rethink my participation in self-representational practices and the attention economy that these practices often get performed within. I had previously been calling my abilities to love myself and to care for myself into question, as grief, depression, and the toll of what feels like many muddy months have insisted on emerging and have persisted. I felt pretty down anytime I saw a post about motivation being bound to properly caring for oneself. Affirmations about one's body seem to get too easily attached to the concept of adequately loving oneself. Even online posts that choose to reclaim the less-desired parts of "the self" seem to imply that this sort of reclamation is necessary in the first place for the processes of self-love/-care.

I start this piece with two photos. In the first one, I posed for the camera and an ex-partner photographed. In the other, Sally posed for the camera, and I shot her photograph. I wanted to think about these two images in a sort of serial-like fashion because, for me, their relationship complicates the seamless understanding of self-representational praxis. These images hold layered meanings for myself as I had my picture taken by someone I lost, and I returned to photographs like this one with many different emotions. As I reflect on loss, I too reflect on an image of myself. I then photographed an image of another, post-loss, as a way of working through some of the grief I feel about that time of my life.

I include a photo of myself and a photo of Sally because our relationship, as depicted here, pushes something about the "self." Neither of us takes up self-love or -care in her interactions with the other in the same way that, say, capitalism would define it. For me, we can cancel plans as quickly and contentedly as we can spontaneously get together. We give each other a type of space that implies a different kind of embrace—one that doesn't ask for certain, definable behaviours of the self anyway. I love it. I guess I am trying to push away from the idea that self-love and self-care have to be definable as sets of actions or interactions. Self-love or -care is not going to the gym or loving your body or falling in love with yourself. It's just endurance sometimes, and it's just difficult and not always legible as anything oftentimes. We want to lie in bed and eat nothing and have those things be OK. We want to feel apathetic about change and growth and have those feelings be OK, too.

The conversation around self-love/-care is contemporary and crucial. It is difficult to go onto a social media platform (Instagram, Twitter, Pinterest, even Spotify, and so on are perfect examples) without coming face-to-face, literally, with someone expressing self-confidence, body positivity, and a desire to rethink how to smash the patriarchy, generally. Immediately, it's easy to figure out why the conversation is essential. It raises a feminist discourse online, arguably finding a rightful place, reaching large audiences. And the more feminists, the better. Social media posts about self-love/-care are important also because they help to craft and reshape beauty standards, definitions of love and care and community, and interactions with ourselves, each other, and all things around and among us.

Especially when thinking through the alternative—which presents dread for the representation of the self and its bodies—self-affirmation becomes not only good for us but urgent and necessary for our survival as well. Or especially when thinking about the role of media in mainstream politics, self-affirmation online can serve as a significant distraction, a necessary moment of feeling and community, a pause for reflection. However, on this thread, we might also locate the recognition that self-affirmation might not merely be definable as being "healthy" or feeling beautiful—or even that accepting one's own body is necessary for self-love or self-care.

The Internet's health and fitness cultures can be very unhelpful for this reason. The Internet's white feminist discourse is harmful for this reason, too. Posts or quotes which equate self-love and -care only to personal growth, falling in love with your body (again), "healthy" behaviours and habits and routines, losing weight, staying active and motivated and inspired, and so on miss a large margin of one's experience of the self—not to mention the objects, interactions, and feelings that "the self" experiences.

I want to key in on the term "influencer," here, as a way of calling attention to our digital culture and the systematic reach of certain peoples' profiles, accounts, networks, and so on. Scrolling through Instagram feeds, for example, a user might find influencers who will write about embracing who they are and celebrating that process of acceptance. These posts reach a lot of people—a lot of people that are reading, watching, listening, learning, being influenced, and acting on that influence. While celebrating acceptance is undoubtedly necessary, we should be more cautious or wary of who we are celebrating and why. What image repertoires do they fit? How or why do these repertoires exist in the first place? And what harmful dynamics might they be reinforcing?

We need to leave—and make—room for those who are grieving, mourning, struggling, not in a place to talk about it, not in a space to share. Posting photos of healthy food or working out is *great,* sure, OK. However, that should not mean that acts like this should then automatically become definable under, or worse, as, self-care, and indeed, these acts should not become synonymous with loving yourself or caring for yourself. There is an urgency for care and for love that gets erased in mainstream representations of loving and caring for the self when the focus gets continuously placed on particular bodies, on particular narratives, on particular objectives. And when focus gets placed repeatedly on particular images, definitions get shaped, and self-love/-care rhetoric can be harmful to those who do not or are unable to fit these descriptions.

One can feel apathetic about one's body and still love and care about oneself. And this is a fundamental distinction, I think.

Two valuable articles for me when rethinking how I conceive of myself, and how and when and where I demand love and care, are Scaachi Koul’s “I Shouldn’t Have To Lose Weight For My Wedding. So Why Do I Feel Like a Failure?” and Johanna Hedva’s “Sick Woman Theory.”

Scaachi Koul wrote her recent article for The Reader and in it, attentively critiques the mainstream body positivity discourse that has been circulating especially for the past two years. @scaachi writes, “My personal conversation with my body hasn’t yet progressed far enough to the point that I love what I have… I just want apathy—to feel nothing about my body at all, to be merely grateful that it functions as I require, that I put clothes on it (when forced), and food in it when necessary (surprisingly often!). Love, like hate, requires too much active effort for something I don’t even want to deal with.” Is your body fed? Are you safe and nurtured and nourished (nourishment coming from more than material items)? And do you feel supported? Do you need support and are you able to acquire it? Do you have spaces where you can feel positive things and can share in those feelings? These are questions we should be asking ourselves and each other.

In "Sick Woman Theory," Hedva writes that "the most anti-capitalist protest is to care for another and to care for yourself. To take on the historically feminized and therefore invisible practice of nursing, nurturing, caring. To take seriously each other's vulnerability and fragility and precarity, and to support it, honor it, empower it. To protect each other, to enact and practice community. A radical kinship, an interdependent sociality, a politics of care." We need to pause for serious reflection and think about who must shrink from, who has historically claimed, and who now gets to reclaim self-love and self-care. Unfortunately, Instagram takes numerous posts down for "disobeying" the community guidelines of the platform—this is especially the case for non-binary folx and emerges as a severe barrier for participation in self-representational practices. When thinking about Instagram or Facebook less as fluid social media platforms and more as spaces representative of systems with algorithms and surveillance and collectible data sets, it is also important to remember that there is a privilege in feeling able to represent yourself freely in these spaces.

A really great song to listen to on this thread is Blood Orange's "Dagenham Dream." The song's outro is voiced by trans rights activist Janet Mock and cause for critical thought:

"Like, growing up I have always heard or like, I was always hyperaware of the things that the people around me who were charged with my care or told me, like, be silent or be quiet or be ashamed or hide or perform a version of myself that wasn't really me. And so, I think that through my life I've always been hyperconscious and aware of not going into spaces and seeking too much attention. Um, because part of survival is, like, being able to just fit in, to be seen as normal and to, like, quote-unquote belong. But I think that so often in society in order to belong means that we have to, like, shrink parts of ourselves."

I often remember and return to activist and celebrity Rowan Blanchard’s Instagram post from March 22, 2018. In the wake of the Trump administration, and its unsurprising illumination of pre-existing and ongoing harmful ideologies, actions, and violences, Blanchard writes a caption for a Boomerang video of her dressed in leather, with a bold red lip. She writes: “Very interested in cutting my hair and fixing on my appearance during the ‘revolution’ as a survival way of temporarily fulfilling, focused distraction—girls/women/nb people exercising whatever autonomy over our own bodies we have left—whatever that means” (emphasis mine). Blanchard places a radical emphasis here on the precarious autonomy of girls, women, and non-binary folx by combining her specific mode of address with a photo of her participating in shared beauty conventions. Moving away from the white feminist discourse which focuses on reclaiming a particular female body through historically “clean” and “healthy” processes, Blanchard instead marks beauty practices as necessary for survival for certain bodies in terrifying times.

It's OK not to be OK. It's OK to feel unsure or ambivalent about, or angry or unhappy with something about yourself. It's also OK to feel confident and content and fulfilled with what you see and how you represent yourself. The problem I want to call attention to emerges when bodies that are always already accepted, embraced, cared about/for, privileged, and so on draw attention to their ability to self-embrace, to self-accept as the model of the ability to embrace and accept and love and care for the self.

Survival and its connection to "the self" are deeply embedded, enmeshed, and entangled in lived experience and reflection and description. Experience is multiplicitous. Reflection, complex. Description, fraught amidst a myriad of tremors of revolution that lie just as much "inside" the self as materialized around it.

Sally, if you're reading this, I think you're the coolest! Thank you for everything.

For Children and (Young) Adults:

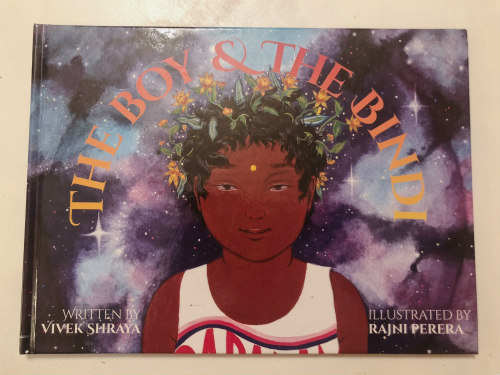

The Boy & The Bindi is a children's book written by Vivek Shraya and illustrated by Rajni Perera. Shraya writes poignantly about childhood, gender expression, and belonging. Perera illustrates with breathless detail, expressing in soft strokes, bold hues. The book is beautiful and important in its provision of a narrative representative of Shraya's experiences and expressions of difference.

You can follow @vivekshraya on Instagram and check out her website, where she has a number of stellar books available for all ages!

References

@rowanblanchard. "Very interested in cutting my hair..." Instagram, 22 March 2018, https://www.instagram.com/p/BgoxvWaFn4h/?hl=en&taken-by=rowanblanchard.

Blood Orange, "Dagenham Dream." Negro Swan, Domino Recording, 2018.

Hedva, Johanna. "Sick Woman Theory." Mask Magazine, 19 January 2016, http://www.maskmagazine.com/not-again/struggle/sick-woman-theory.

Koul, Scaachi.“I Shouldn’t Have To Lose Weight For My Wedding. So Why Do I Feel Like a Failure?” 11 August 2018, https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/scaachikoul/wedding-dress-lose-weight-loss-body-image-positivity.

Shraya, Vivek. The Boy & The Bindi. Arsenal Pulp Press, 2016.

About Tasha:

About Tasha:

I am the "T" in DLTK! In my spare time, I love to hike, read poetry, and hang out with my two cats. You can connect with me here.